Notes from the

Curator's Office:

Magic

& Teaching

|

Houdini

was a great escape artist, but not so good a conjurer.

|

(04/09) Houdini was a lousy

magician. I know that this one statement will probably get me

hate mail from the four corners of the globe, but it's the conclusion

you reach after reading Jim Steinmeyer's book Hiding the

Elephant.

Though most people would not recognize his name,

Steinmeyer is one of the most brilliant, modern creators of magic

tricks (he's the guy who taught David Copperfield how to make

the State of Liberty disappear). Steinmeyer has built tricks for

some of the best in the business, including Lance Burton, Doug

Henning and Rick Thomas.

In addition to making magic tricks, however, Steinmeyer

is also a student of magic history. His book tells about the golden

era of magic starting in the mid-19th century and running through

the 1940's. Houdini lived in the middle of this time period from

1874 to 1926.

What interested me in Steinmeyer's book, however,

was not just the history of magic, but some parallels that can

be drawn from it to learning and education. I think the difference

between a great teacher and a mediocre teacher is a lot like the

difference between a great magician and a mediocre magician. Most

teachers have the same basic knowledge to give to students in

a similar way to how all magicians have the same basic illusions

to display. What makes a magician great is how he presents his

illusion. The same is true in teaching.

Before we get into that discussion, however, we

need to go back to Houdini.

Houdini

as a Conjurer

Despite what I've said up to this point, after reading

Hiding the Elephant you don't come to the conclusion that

a Houdini show was dull or boring. Not at all. As an escape artist,

a subset of magic he practically invented, he had no equal. As

a child Orson Wells, who wasn't a bad magician himself, saw Houdini

perform his escapes and pronounced them "thrilling." However,

when Houdini's act moved on to conjuring - that is making things

appear and disappear - Wells was disappointed. "It was awful stuff,"

he recalled.

Why did Houdini have such a hard time with this

type of magic? It required a finesse which he simply didn't have.

Steinmeyer writes in his book "Watching him play the part of an

elegant conjurer was a bit like watching a wrestler play the violin."

Perhaps the best example of Houdini's problem in

this area is the story of the vanishing elephant.

|

New

York's largest theater in 1918, the Hippodrome.

|

Houdini was well aware of his shortcomings as a

magician and very much wanted to show the public and his fellow

prestidigitators that he was a world class conjurer. In 1918 he

got his chance. Early that year Houdini was engaged for 19 weeks

as a feature player at New York's Hippodrome. At that time the

Hippodrome was the largest theater in the city seating almost

6,000 people. The immense stage featured lavish spectacles complete

with circus animals, diving horses, dancing girls and choruses.

The entire stage could be turned into a massive pool that was

sometimes used to re-stage famous naval battles.

According to Houdini, it was while he was watching

the elephants perform at the Hippodrome that he had a wonderful

idea. One of the most impressive feats of the conjurer was to

make a live animal appear or disappear. Because magicians were

constantly traveling from location to location, the creature used

was usually something small like a bird, rabbit or dog. Some of

the more impressive tricks, however, had involved a larger animal

like a donkey. Here Houdini would have elephants available to

him for the entire 19 weeks he was working at the Hippodrome.

Suppose he made one of them disappear? He would be considered

the greatest conjurer of all time!

The

Elephant Trick

It took Houdini several weeks to work out the details

(in conjunction with Charles Morritt, another magician and illusion

designer), but by the time he debuted at the Hippodrome the trick

was ready.

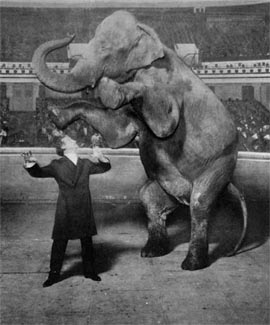

|

Houdini

and Jennie in a publicity still.

|

Houdini would appear on the stage and Jennie, a

10,000 pound elephant, would be led out by her trainer. Houdini

would introduce her as "The Vanishing Elephant" while 15 assistants

rolled a giant box out onto the stage. The box was eight feet

high and eight feet wide and probably about fourteen feet in length.

It was also elevated more than two feet in the air so that the

audience could see underneath it and know that the elephant wasn't

going through a trap door in the floor. Houdini would have the

small end of the box turned to face the spectators. He would then

open doors on either end so they could see through it and be assured

it was empty.

The box would then be turned so the long part faced

the audience and a ramp would be put up by the door. The trainer

would lead the elephant inside and the doors would be closed.

The assistants would then turn the box again so it faced the audience

and the doors would be opened. The spectators looking through

could see out the other side. No elephant. It had apparently vanished.

The trick was heavily lauded in the press and publicity

for the Hippodrome. However for the audiences actually in attendance

in the huge theater the illusion was mostly a flop. Why? Not because

it was a bad trick, but for the reason that Houdini didn't present

it right. He didn't prepare the audience for what was about to

happen. Even worse, very few in the audience actually got to see

the illusion. As one observer at the time wrote:

The Hippodrome being of such a colossal size,

only those sitting directly in front got the real benefit of the

deception. The few hundred people sitting around me took Houdini's

word for it that the "animile" had gone - we couldn't see into

the box at all!

Colonel

Stodare's Sphinx

|

The

now demolished Egyptian Hall in London exhibited Stodare's

"Sphinx" illusion.

|

Compare this with the "Sphinx" illusion presented

by an earlier Victorian magician named Colonel Joseph Stodare.

Stodare was working a theater called Egyptian Hall in London.

The theater had once been a museum and was adorned with Egyptian

sculpture and hieroglyphics. When a new illusion mechanism became

available to him, Stodare decided to work the theater's theme

into the trick. For weeks before unveiling his illusion, Stodare

placed cryptic ads on the front page of the London Times

like "The Sphinx has left Egypt," and "The Sphinx has arrived

and will soon appear." When he finally premiered the trick, the

hall was packed with the curious.

When the curtains were opened the audience was greeted

with a small, round, thin, bare three-legged table with no tablecloth.

Stodare would walk onto the stage carrying a fabric covered traveling

case about a foot high, wide and deep. After placing it on the

center of the table, he would open the hinged doors in front to

reveal what appeared to be a sculpture of a head in Egyptian headdress.

Stodare would move to the edge of the stage, then

command, "Sphinx, awake!" The eyes of the sculpture would pop

open and look around, slowly appearing to become aware of its

surroundings. Suddenly it became clear to the audience that they

were viewing a disembodied human head. Stodare would ask it questions

and the Sphinx would answer. The head finally gave a short speech

and closed its eyes. Stodare would then return to the table, close

the doors and spend a moment reflecting on the mysterious nature

of the Sphinx. When he reopened the box the head was gone, replaced

with a pile of ashes. Stodare then carried the box to the edge

of the stage so the audience could get a better look at it.

The Egyptian Hall rang with applause and the next

day the papers were filled with acclaim. "The Sphinx is the most

remarkable deception ever included in a conjurer's programme,"

proclaimed the Daily News. The following month Stodare

found himself performing for royalty at Windsor Castle.

Why did Stodare's illusion work so well and Houdini's

didn't? From a technical point of view, both tricks were amazing

for their times. One, however, created a sense of wonder with

the audience and the other didn't.

|

A

drawing of Stodare's Sphinx Illusion.

|

First, Stodare got people engaged in thinking about

the illusion before he did it. His cryptic ads caught their imagination.

They made people think about the sphinx. What did they already

know about it? What did it mean that it was coming to London?

Secondly, Stodare's presentation had a story arc.

He placed the sculpture onto the table. He awakened it. He engaged

it in conversation. Finally he closes his presentation reminding

his audience about the mystical nature of the sphinx and when

he opens the box again it has turned to ashes.

Finally, Stodare not only made sure the entire audience

could clearly see the Sphinx during the performance, at the end

of the performance he carried the open box to the edge of the

stage so they could get a better look. This way they could see

it with their own eyes and be absolutely sure it was empty.

This differed from what Houdini did with the elephant.

He did plenty of advertising, but it didn't really entice people

to think about elephants the way Stodare's cryptic statements

did about the Sphinx. Houdini had no story behind his trick; he

simply shoved the elephant in the box and presto it was

gone. Finally, and most importantly, lots of people couldn't really

see the elephant disappear. They only knew it had because Houdini

had told them so.

Lessons

& Tricks

What does this have to do with teaching? Everything.

A good lesson is like a good magic trick. As Stodare enticed his

audience with his riddle-like statements even before they got

in the theater, a good teacher must grab the student's attention

at the beginning of the lesson. I've heard a couple of terms for

this, but where I got my degree they called it "the hook."

Hooks can be as simple as an intriguing story, joke

or riddle or as complicated as a fun quiz or video clip. The key

is that they grab the student and are somehow linked into your

subject. The best hooks also "activate" the student's current

knowledge. That is, they remind the student of what he already

knows about a subject so he will be more prepared to learn the

new material.

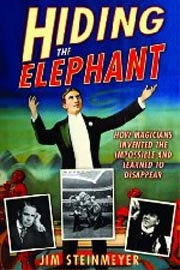

|

Jim

Steinmeyer's book on the history of magic tells you something

about education too.

|

Stodare's trick had a whole story to it. A good

lesson, in the same way, is like a story. It has a beginning,

a middle and an end. There is a flow to it. One item logically

follows another in quick succession.

A good lesson may even have elements of drama in

it. While this is easier when dealing with social studies and

history which lend themselves to good stories, it is also possible

with the sciences. A couple years ago I integrated a 40-year-old

science fiction TV drama about scientists lost in time into learning

the mechanics of reading clocks and calendars for my 4th grade

class (Time Tunnel to Fourth Grade).

It was one of the best units I ever created and one of the most

fun and memorable for my kids.

A good storyteller also makes sure that he gives

his audience the necessary background information needed to understand

his tale before launching into it. He needs to make sure his listeners

aren't lost from the get go.

This kind of thing sounds obvious, but when doing

a lesson many teachers find they have assumed their students have

come to class with more background information than they actually

have. It is very easy for a 40-year-old teacher to forget that

his 4th grade students weren't even alive a decade ago. They might

well know that Hillary Clinton ran for President, but not be aware

that her husband, Bill, actually was the president back

in the 90's.

Constructing

Your Own Knowledge

Finally, in a good lesson, the student must be able

to see (or discover) for themselves the point of it. In education

we call this "constructing your own knowledge." Stodare's audience

was able to construct their own knowledge about the Sphinx disappearing

because they saw it for themselves, not because he told them it

disappeared. The same idea works in a classroom. For example,

in a science lesson a good science teacher doesn't just tell his

class that you can separate hydrogen and oxygen from water by

electrolysis. He demonstrates it for them in front of their own

eyes. Even better, if he has the time and the equipment, he lets

them do the experiment and figure out how the reaction works by

themselves, rather than just giving them the information. People

remember things they have done and have figured out on their own.

Things they've just heard about they often forget.

|

A

fall leaf can always be a source of wonder to a student

if presented right.

|

A lesson done right, like a magic trick done right,

leaves the audience with a sense of wonder. In his book, Steinmeyer

tells a story about how as a boy he was fascinated with why the

leaves of tree turned red in the fall. When he reached the 4th

grade, his teacher told him that the chlorophyll in the leaf dies

in the autumn, leaving a bright color. "I appreciated that the

mystery had been completely solved," he writes, "and I could stop

worrying about it." However Steinmeyer also writes that "Unfortunately,

science often serves the purpose of actively teaching us to stop

wondering about things, causing us to lose interest."

I submit that this is true of science, and learning

in general, only if it is done wrong. Good science, like good

learning, answers questions at the same time it poses more for

the student to think about. Wondering what it would look like

to ride a bicycle at the speed of light helped Einstein

to create his theory of relativity. Wondering why apples fall

helped Newton think about how the laws of gravity and motion might

work.

Like good magic, good teaching should always leave

the viewer with a sense of wonder.

Copyright Lee Krystek 2009.

All Rights Reserved.