The Mystery

of the Voynich Manuscript

|

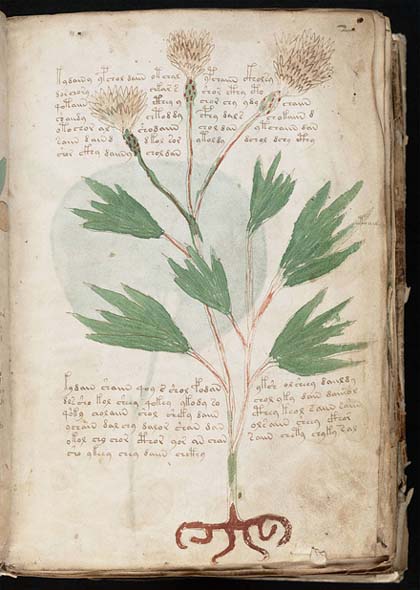

A

page from the Voynich manuscript showing the strange writing

along with a color illustration.

|

In 1912

Wilfred M. Voynich was going through the archives of the Nobile

Collegio located at Villa Mondragone looking for some old, potentially

rare books. In a dusty chest he found a codex that wasn't just

rare, but also a puzzling enigma that has had researchers scratching

their heads for most of the last century.

The

Voynich manuscript is an illustrated, hand-written book around

240 pages in length (depending on how you count the book's foldout

sheets). It measures about 9 ½ inches tall, 6 ½ inches wide

and 2 inches thick. Its leaves, which have been carbon-dated

to the early 15th century (1404-1438), are made of vellum (calf

skin) and are covered not only with script, but also vivid,

color illustrations containing herbal, astronomical, biological,

cosmological, and pharmaceutical information. One of the features

of the book is that it has fold out pages that allow for extended

diagrams. All this, in of itself, would not make the manuscript

particularly unusual. In many ways it resembles other pharmacopoeias

(books containing instructions on making medicine) from the

medieval period. What makes it a mystery is that almost all

the text in the book is written in a language and script that

is totally unknown to the modern world.

Now

this doesn't mean it is written in a language like Rongo

Rongo where the meaning of this once well used prose has

simply been lost. For example, with Rongo Rongo we don't know

how to read it, but we do know it was used on Easter Island

until the 1860s and represents the spoken language Rapa Nui

which was used on the island.

No,

the script in the Voynich manuscript is written in a language

we know absolutely nothing about. No other letter or book that

we are aware of is written in this language. And it's not just

the language that is unknown, the letters themselves do not

seem to correspond to any known script. Most European languages

at least use most of the Latin alphabet, but the Voynich manuscript

does not. Neither does it seem to use any of the Arabic or Cyrillic

or Hebrew letters.

There

are also alot of other things we don't understand about the

Voynich manuscript. We don't know who wrote it. We can't identify

with any assurance any of the plants pictured in it and we don't

know anything about its origins. And although there are a handful

of notes on pages that appear to be written in Latin script,

we have no idea of what those mean, either.

History

|

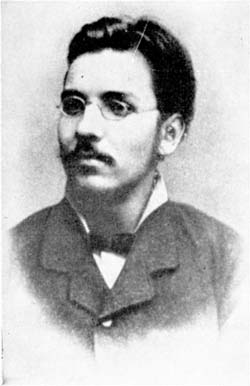

Polish

book dealer Wilfred M. Voynich.

|

What

we do know is that there is a letter from 1666 that was found

inside the cover that states that the manuscript had once belonged

to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) and that he

paid 600 gold ducats to buy it. After Rudolf, the book seems

to have then been passed around until it ended up in the hands

of Georg Baresch, an alchemist living in Prague during the 15th

century. In 1639 Baresch wrote a letter to Athanasius Kircher,

a Jesuit scholar from the Collegio Romano, concerning the document.

Baresch's letter, the earliest known reference to the book,

tells us at least one important thing: That Baresch was just

as puzzled by the manuscript's writing as researchers are today.

Kircher was a language expert who had published a Coptic (Egyptian)

dictionary and was trying to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Baresch was trying to engage his assistance in translating the

manuscript and sent him several samples of the text.

While

Baresch was alive he refused to send Kircher the book itself,

but after his death Kircher acquired the codex from Jan Marek

Marci, a friend of Baresch. It is unknown if Kircher made any

progress on the translation, but the book wound up with much

of the rest of his library in the hands of the Collegio Romano

in Italy where Voynich found and purchased it in 1912. After

Voynich's death, his widow inherited the book. Eventually, antique

book dealer, Hans P. Kraus bought it and donated it to Yale

University, which still owns it today.

There

has been some speculation through the years that the author

of the book was the English philosopher, Franciscan friar and

writer Roger Bacon (1214-94). Marci mentions this possibility

in his 1666 letter to Kircher, and Voynich believed it too,

but no proof of a connection to the famous writer has ever been

found.

The

Illustrations

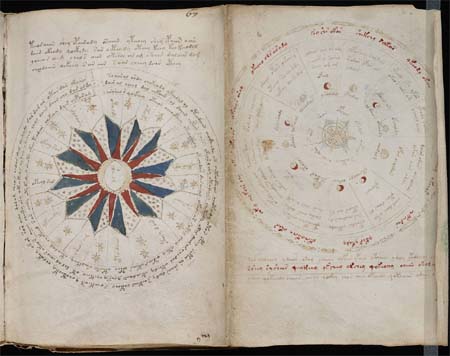

Since

the language is unknown, the illustrations are the only way

to tell what each section of the book is about. These too, however,

are extremely mysterious. None of the plants shown in the pictures

can absolutely be identified. Some astrological symbols can

be discerned, but not all of them. Other illustrations, containing

figures of naked women in tubs connected by an elaborate system

of pipes, seem to have no meaning at all. It does seem likely

that the illustrations were originally outlined in black ink

and the colors added at a later time by a less talented artist.

Is

It Encyphered?

Many

attempts have been made to understand the language in which

the book is inscribed. One theory is that the writing is some

secret code or cypher. The text of the book could have been

written in a standard European language, let's say Italian,

then translated into the cyphered text by assigning each letter

of the Latin alphabet to one letter in a new made up alphabet.

Without a key to tell you which letter was mapped to which,

reading the text would be extremely difficult.

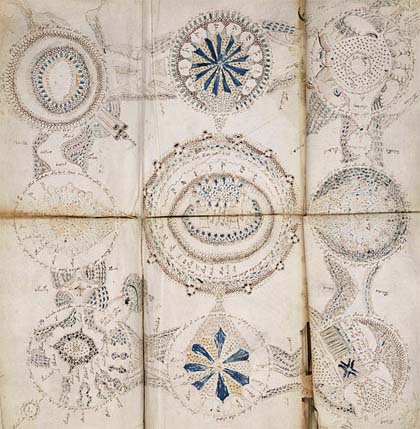

|

One

of the foldout pages in the manuscript.

|

The

science of cryptography was becoming systemized in Europe at

about the same time the manuscript was written, so it seems

possible that the author may have decided to keep his book secret

by encrypting it. However, there are also some problems with

this theory.

A simple

substitution cypher, as described above, would also be very

easy to break with modern methods. These have been applied to

the Voynich manuscript and yielded nothing. In fact, attempts

to decrypt the codex assuming it used a number of more complex

encryption methods have failed, too. Even without being able

to decrypt the book, many cipher systems can be eliminated because

such ciphers produce text with certain characteristics not seen

in the manuscript.

A

Natural Language

Another

possibility is that the text was written in a little known-language

for which a new phonic alphabet was created. Analysis of the

frequency that the letters and groups of letters appear suggest

that the document is indeed a natural language. In 1976, James

R Child of the National Security Agency suggested that the document

was written in a "hitherto unknown North Germanic dialect".

In 2003, Zbigniew Banasik proposed that the manuscript is written

in the Manchu language. Other experts have suggested that the

manuscript may be in an unknown Chinese or Vietnamese dialect

because it has similar characteristics, including the frequency

of doubled and tripled words.

However,

none of these ideas have been proven, and the source and meaning

of the script remains unknown.

There

is the possibility that the language used in the Voynich manuscript

is an artificially-constructed language (that is one in which

the grammar and vocabulary have been consciously devised rather

than having arisen naturally). However, at the time of the writing

of the manuscript, the idea of a constructed language was not

yet well known, which makes this possibility seem unlikely.

Is

It a Fraud?

The

book is so odd that many people think that it is some kind of

hoax. Who might be behind such a forgery? Well, Voynich is one

of the first possibilities most people consider. As an antique

book dealer, he would have the knowledge and means to fabricate

such a document. If he could have convinced people that the

author was Roger Bacon, the value of the manuscript would have

been immense. Even though the pages have been carbon dated to

the 13th century, it is possible that Voynich found blank leaves

created in that period but never used. The iron gall ink used

in the writing can't be dated and could have been applied at

any time, so the possibility of a modern hoax can't be ruled

out completely.

However,

the likelihood of finding that number of unused vellum sheets

all from the same era seems to make a modern hoax very unlikely.

Also, the 1639 letter from Baresch to Kircher concerning the

manuscript proves that such a document did certainly exist during

this period, even if we can't absolutely prove that the Voynich

manuscript is the book being referred to in the communication.

|

There

still remains the possibility that the document is not a modern

fraud, but an old one. In 2003 Gordon Rugg, a psychologist who

teaches in the computer science department of Keele University

near Manchester, England, advanced the theory that the book

was simply gibberish. A clever forger could have produced the

document by using a table of word prefixes, stems, and suffixes,

which would have been chosen and merged by means of a paper

overlay with holes. Such an overlay ( called a Cardan grille),

was used starting around 1550 as an encryption tool. Using such

a tool would allow the creator of the document to quickly produce

something that looked like a real language, but actually had

no meaning.

Why

would he do that? Rugg thinks that it was for money. You might

be able to sell such an indecipherable mysterious book to someone

who thought it might contain secret knowledge when decoded.

Indeed, the Voynich manuscript was sold to Roman Emperor Rudolf

II for the equivalent of $30,000 today. Rugg's prime suspect

for this skullduggery is Edward Kelley, a member of the court

of Elizabeth I who made himself part of the household of the

queen's astrologer, John Dee, and supposedly acted as a medium

for angels. In experiments, Rugg claims that by using a Cardan

grille he was able to produce text that looks a lot like the

Voynich manuscript, but actually was just gibberish.

Other

researchers disagree. In 2013 Marcelo Montemurro, a theoretical

physicist from the University of Manchester, led a study where

he used a computerized statistical method to analyze the text.

The results according to Montemurro showed that "content-bearing

words tend to occur in a clustered pattern, where they are required

as part of the specific information being written. Over long

spans of texts, words leave a statistical signature about their

use. When the topic shifts, other words are needed." The Voynich

manuscript, like real languages, shows just such a pattern.

Even

Rugg conceded that it is possible that although much of the

document might be rubbish constructed by the use of the tables

and Cardan grilles, the remaining part might contain an encrypted

message.

Possible

Translation

In 2014

Stephen Bax, a professor of applied linguistics, claimed he

had decoded a few of the words by starting with the proper names

of some of the pictures. "The manuscript has a lot of illustrations

of stars and plants. I was able to identify some of these, with

their names, by looking at mediaeval herbal manuscripts in Arabic

and other languages, and I then made a start on a decoding,

with some exciting results," explained Bax.

Despite

Bax's enthusiasm, it should be noted that a number of other

experts have claimed to have decoded small parts of the Voynich

manuscript, but none of these was proven to be successful with

the whole document. We will have to wait and see if his method

finally solves the enigma of the Voynich manuscript, or if it

is simply another dead end.

Copyright

Lee Krystek 2015. All Rights Reserved.